Child treated at a hospital in Ghouta after what a Syria medical relief group claims was a chemical attack.

General News

Scientist accused of developing Syria’s chemical weapons program traced to Edmonton

Published

11 months agoon

By

NaijaGazette

Early on Aug. 21, 2013, Syrian government forces fired rockets loaded with the nerve agent sarin into the rebel-held Ghouta district of Damascus.

As the chemical clouds spread, residents began to froth at the mouth. Fluid oozed from their eyes and noses as they convulsed and suffocated.

The Ghouta gas attack killed up to 1,400 people, many of them children, and was the latest display of the horrors of chemical warfare.

Ten years later, Global News has traced a scientist accused of helping Syria develop its chemical weapons program to an Edmonton suburb.

Child treated at a hospital in Ghouta after what a Syria medical relief group claims was a chemical attack.

De-classified Canadian government documents allege that Ahmad Haytham Alyafi made a “significant contribution to the manufacturing of chemical weapons.”

From 1974 to 1994, the chemical engineer worked at the military-run centre that produces chemical weapons for the Syrian regime, federal officials wrote in the documents.

Alyafi “set up a plant he knew would manufacture chemical weapons; he therefore contributed significantly to their production,” according to the documents, which call his role “indispensable.”

But when rescue workers were collecting bodies in Ghouta a decade ago, Alyafi was living in a 2,500-square-foot home on a cul-de-sac in Edmonton’s west end, the records show.

“Mom and dad have been living with us at our house in Edmonton since the spring of 2013,” Alyafi’s son wrote in a 2019 letter sponsoring his parents for permanent residence in Canada.

“My dad picks up the kids from school daily and they spend time with them on homework after school time,” wrote the son, who works in the Alberta construction industry.

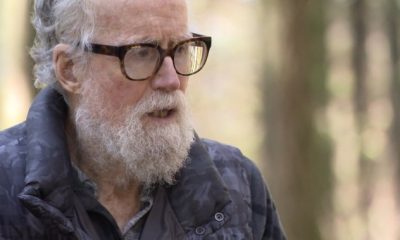

Profile photo from Facebook page of Ahmad Alyafi.

Immigration records from 2019 list the Syrian scientist as “currently residing in Canada.” The address he used was a four-bedroom home in Edmonton’s Glastonbury neighbourhood.

Whether he remained in Edmonton was unclear. The home is currently staged and up for sale. Neighbours recalled seeing Alyafi, but not for several months.

His cell phone has an Alberta 587 area code and is still active, but he did not answer or respond to text messages or emails.

The federal agencies that investigated Alyafi declined to discuss his case.

“I have no family left in Syria,” Alyafi wrote in a statement as part of his bid to immigrate to Canada.

“My life is my son and my grandchildren. They need their grandparents to give them extra emotional and mental development.”

He denied ever making chemical weapons, but Canadian government documents tell a different story.

The first large-scale chemical weapons were used by German forces in 1915. By the end of the First World War, chemical weapons from all armies had claimed at least one million casualties, 12,000 of them Canadians.

The 1925 Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemicals in armed conflicts, but Syria secretly began a program in the 1970s after losing a war with Israel.

UN investigator takes sand samples near suspected chemical rocket, Ain Terma, Syria, Aug. 28, 2013.

AP Photo/United Media Office of Arbeen, File

Assigned to the task was the innocuously named Scientific Studies and Research Centre (SSRC), which was “responsible for the development of nuclear, biological, chemical, and missile-related technology,” a Canadian government report on Alyafi alleged.

SSRC scientists were “a key component of the chain of command — they developed and produced chemical weapons, which were later used against the Syrian population, including civilians,” it said.

During his two decades at the SSRC, Alyafi held a “senior position,” according to the results of an investigation.

Alyafi was investigated by CSIS and the CBSA.

Global News

A Canadian Security Intelligence Service report alleged that “Alyafi was involved in the start-up phase of the SSRC’s pilot plant … the purpose of which was the production of chemical weapons.”

A subsequent report by the Canada Border Services Agency’s National Security Screening Division alleged Alyafi spent 3-1/2 years conducting research for the “pilot plant.”

Alyafi is “a former director … of the SSRC … responsible for developing and producing chemical and biological weapons; in addition, the information indicated that the applicant was involved in the SSRC’s pilot project to produce chemical weapons,” the CBSA wrote.

He held “high positions of importance,” including Project Manager and Technical Director, and remained with the centre for 20 years, and later became Syria’s vice minister of industry, the report said.

What was the role of an Edmonton MP?

The CSIS and CBSA reports were produced in 2018 after Alyafi applied for permanent residence in Canada. Parts were blacked out “for reasons of national security.”

The records also show that in 2018, the office of Conservative MP Kelly McCauley contacted immigration officials several times about the case. Alyafi’s Edmonton address is in McCauley’s riding.

McCauley said he was unaware of the allegations against Alyafi until contacted by Global News. “These are not shared with us,” he said. “All we can do is check on applications.”

Headquarters of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, OPCW, The Hague, Netherlands. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong).

He said his office first checked on Alyafi’s file in September 2018. In February 2019, his office asked for an update, and in May 2019, it forwarded documents to the immigration department.

But Alyafi’s application for permanent residence was rejected due to his “contributions to Syria’s chemical weapons program.”

The letters denying him residence said he had a “key role” in installing a plant he knew was being built to manufacture chemical weapons that were “to be used in the future for ill purposes.”

He was deemed a danger to the security of Canada. The CBSA said that, given his experience, he could “pass this knowledge on to others producing chemical weapons.”

Police officer next to the bench where Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were found in Salisbury, England, on March 4, 2018.

Thomas Belk/Solent News & Photo Agency via AP

The Russian government’s poisoning of double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the United Kingdom in March 2018 involved the use of the nerve agent Novichok and “measures should be taken in order to prevent such devastating incidents,” the CBSA wrote.

More recently, the reckless invasion of Ukraine by Syria’s top ally Russia has stoked fears President Vladimir Putin may resort to chemical attacks.

Alyafi challenged the decision in the Federal Court and lost in 2021.

Syria amassed an estimated 1,000 tonnes of the chemical warfare agents sarin, VX and nitrogen mustard by 2014, according to Jane’s Intelligence Review.

The UN has been trying to dismantle the program. As part of the effort, the SRCC and its staff have been sanctioned by Canada (under its French acronym CERS) and other countries.

The Trudeau government has decried Syria’s use of chemical weapons as “morally reprehensible” and said it “wholly supports efforts to ensure that perpetrators of such crimes are held to account.”

Chemicals from Syrian weapons stockpile to be destroyed at Veolia waste handling plant, Ellesmere Port, U.K., on. Feb 25, 2014.

Paul Cooper / Rex Features

Canada is also a member of the Partnership Against Impunity for the Use of Chemical Weapons.

Federal agencies declined to respond to questions about Alyafi. But he does not appear to have faced any charges in Canada, and there is no official confirmation he was deported.

Alyafi did not respond to interview requests by phone, email, text and social media, but Global News has obtained statements he sent to immigration officials handling his case.

According to the statements, after completing his PhD in chemical engineering at Manchester University in England, Alyafi returned to Syria in 1977 to work at the SSRC.

He was given employee number 162 and told the centre would be producing “a chemical agent that is harmful to humans,” he wrote.

He claimed the toxic agent was “not to be used ever.” Rather, he wrote, it was meant as a “deterrent” against what the Syrian regime claimed were nuclear threats from its enemies.

The chemical agents were meant “to provide the leadership of the country a strategic weapon,” he explained.

By developing chemical weapons, Syria hoped to boost its “negotiating position in any future peace talks that may take place in the Middle East.”

Damaged buildings in Douma, Syria, site of a suspected chemical weapons attack on April 16, 2018. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar, File).

HM

While he said he was disappointed to find out the SRCC was developing a chemical agent, he was legally obliged to work for the centre for 7-1/2 years because it had funded his PhD abroad.

He had to spend an additional 2-1/2 years at the SRCC as compulsory military service, he added.

The only way out was to leave Syria, which would have put his family at risk, he wrote in his statement.

“I was trapped.”

He said his role was to “help in the start up of the plant,” but he denied any role in “strategic decision-making” and said he tried repeatedly to quit.

A statement signed by Ahmad Alyafi, who spent two decades working at the Syrian centre that manufactures chemical weapons.

Federal Court

His team at the SRCC included three majors from the “army chemical war department” who had been sent to the Soviet Union to study, he wrote.

“I have never dealt with a chemical warfare agent,” he wrote. “Of course, I had no part of any discussion on the delivery systems because it is not in line with my role or expertise.”

He said he first tried to leave in 1987, and tried seven more times until his resignation was accepted in 1994. He then went into business, and served as the Vice Ministry of Industry from 2006 to 2009.

In 2010, he said a Syrian-Canadian business association invited him to tour Canada for 12 days. He was in Regina when a “Canadian Security department” officer asked to meet him.

A photo posted on Facebook by the wife of Ahmad Alyafi shows their backyard in Edmonton.

He returned to Canada in 2013 and was again visited by security officers at his son’s home in Edmonton. He said he “discussed my work and role in the SSRC.”

He claimed the officers assured him there was no problem and “from now on your stay in Canada will be plain sailing.” CSIS declined to comment on the alleged incident.

“I clearly state that I am never a danger to Canada and was never involved in strategically manufacturing chemical weapons for any reason,” he wrote.

Syria admitted it had chemical weapons in 2012. While the regime vowed not to use them, reports of sarin attacks mounted. The Ghouta attack in August 2013 was the first confirmation of their large-scale use.

The United Nations Security Council ordered the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons in September 2013. But Syrian forces again used sarin against civilians in the town of Khan Shaykhun on April 4, 2017. Ninety died, 30 of them children.

As it does in Ukraine, Syria’s ally Russia harnessed its state propaganda outlets to spread disinformation about the attack, falsely blaming the UN.

Syrian soldier in Khan Shaykhun, Syria. (AP Photo/Albert Aji).

The regime conducted an estimated 120 chemical attacks, most by dropping barrels filled with chlorine from helicopters. Unlike sarin, which is so lethal that it was banned under the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1993, chlorine also has commercial uses and as a result, is more challenging to regulate.

“Because sarin acts on the nervous system, it disrupts all bodily functions — pupils shrink, mouth and lungs fill with saliva and bodily fluid,” the CBSA wrote in its report on Alyafi.

“Heart begins to slow, blood pressure decreases causing consciousness, bowels and bladder spasm painfully and empty out. Some victims may experience seizures; and sometimes, exposure can be fatal.”

It is particularly harmful to children.

Syrian President Bashar Assad, right, waves to supporters in the town of Douma, in the eastern Ghouta region, Syria, on May 26, 2021. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar).

Alyafi said he had given his “greatest gift in life to Canada” — his son, who is a Canadian citizen.

He said that his factory in Damascus was destroyed during the war, and he knows other SSRC scientists who live in Canada and the United States.

“The bottom line for me, Canada is the country I trusted my son with since he was 17 years of age and now proudly a Canadian citizen and it is his home country and my grandchildren’s birth and home country,” he wrote.

He and his wife want “to join our only son and his family in Canada and to make Canada our home.”

Under the heading intended occupation, Alyafi wrote: “Depending if some of my skills are needed and allowed.”

Stewart.bell@globalnews.ca

Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. All rights and credits reserved to respective owner(s).

You may like

-

Canada’s income gap is growing. Will Budget 2024 help affordability? – National

-

What are midges and why are they swarming Toronto’s lakeside region – Toronto

-

Ontario iGaming wagers hit $17.8 billion in 2023-2024

-

Meet the man who’s lived 30 years in Stanley Park

-

Manitoba’s first CAR T-cell therapy patient declared cancer-free – Winnipeg

-

Extent of damage to Okanagan cherry buds revealed as blossom season arrives – Okanagan

FG trains 40 hygiene promoters on safe water, sanitation practices

Wike vs Atiku: Former Senator, Bwala mocks PDP over current crisis

FMBN restrategising to deliver more houses to Nigerians- MD

Former Golden Eaglets Player Backs Manu Garba For Another U17 World Cup Success

Canada’s income gap is growing. Will Budget 2024 help affordability? – National

EPL: I was so sad – Bastian Schweinsteiger reveals what Mourinho did to him

Cameroon beat Nigeria in opening match

EU debates future regulation of Artificial Intelligence within the bloc

Burna Boy Bags 4 Nominations On 2023 Soul Train Awards

Grassroot Football Teams Pays Congratulatory Visit To Alhaji Salisu Usman Galadima

Nigeria vs Lesotho: Notsi Beef up Squad for Super Eagles